How to Preserve Your Grooved Media

Vinyl, wax, and acetate are the original physical audio media. While we still produce it, it degrades with every use.

Preserving Grooved Media: Safeguarding Vinyl Records, Wax Cylinders, and More

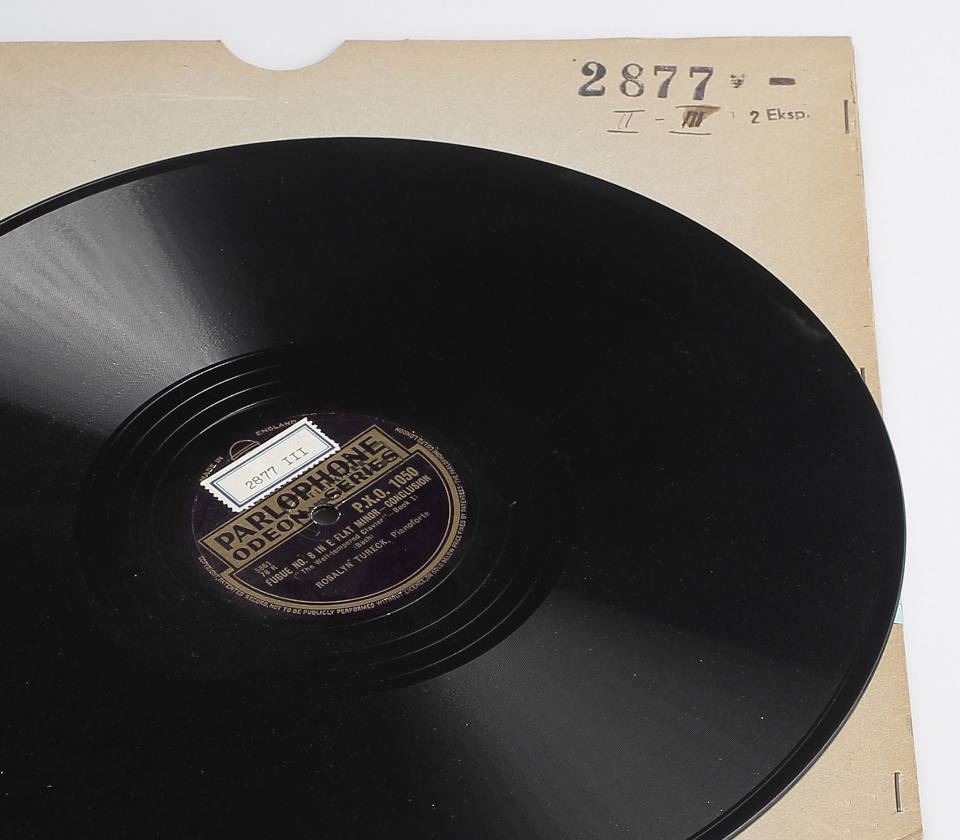

Grooved media—such as vinyl records, shellac discs, lacquer discs, aluminum discs, and wax cylinders—represent a cornerstone of audio history, capturing everything from early 20th-century music to unique home recordings and radio broadcasts. As these formats become relics of a bygone era, with playback equipment growing scarce, their preservation is increasingly vital to protect cultural, historical, and personal legacies. These fragile media, prone to breakage, warping, and chemical deterioration, have lifespans ranging from decades to a century under optimal conditions. Preservation, including archiving contents onto modern media, ensures their sound remains accessible. This article explores the importance of preserving grooved media, details the challenges involved, and provides practical tips for extending their life and safeguarding their audio content.

The Importance of Preserving Grooved Media

Grooved media, spanning from wax cylinders (late 1870s–1929) to shellac discs (1897–late 1950s), lacquer discs (1920s–1970s), aluminum discs (1920s–1940s), and vinyl records (late 1940s–present), store sound as physical grooves etched into surfaces like wax, shellac, lacquer, aluminum, or polyvinyl chloride. These formats hold irreplaceable content: commercial music, oral histories, ethnomusicological field recordings, radio transcriptions, and personal voice recordings. For example, a lacquer disc of a 1940s radio broadcast or a wax cylinder of a family’s home performance may exist as a singular artifact, with no duplicates.

Preserving grooved media maintains access to these sonic treasures as playback devices, like turntables or cylinder phonographs, become obsolete. The Library of Congress notes that proper storage can significantly extend the life of these materials, while neglect accelerates deterioration. Digitizing their contents protects against physical loss, ensuring future generations can hear voices and music from the past. Beyond content, the physical objects—such as a vibrant vinyl LP or a delicately etched wax cylinder—carry cultural value as artifacts of technological and artistic history.

Challenges in Preserving Grooved Media

Grooved media face preservation risks from their material composition, environmental factors, and handling practices:

-

Material Instability:

-

Shellac Discs: Composed of shellac resin with fillers (clay, slate, cotton fibers), these discs are brittle and prone to shattering if dropped. Pre-WWI discs may contain volatile materials, increasing deterioration risks. Laminated shellac discs with cardboard cores are especially fragile.

-

Lacquer Discs: Made of cellulose nitrate or acetate lacquer on aluminum, steel, glass, or fiberboard cores, lacquer discs are susceptible to delamination, where the lacquer shrinks and peels from the core, causing irreversible signal loss. Plasticizer loss produces white, greasy palmitic acid deposits, often mistaken for mold, which can damage grooves. Glass-core discs are extremely fragile and prone to cracking.

-

Aluminum Discs: Uncoated aluminum is chemically stable but soft, with shallow grooves that can be flattened by pressure, distorting or erasing recordings.

-

Vinyl Discs: Polyvinyl chloride or polystyrene discs are softer than shellac, making them vulnerable to scratches, abrasion, and warping under heat or UV exposure. High humidity fosters fungal growth.

-

Wax Cylinders: Early brown wax cylinders (pre-1902) are soft, prone to scratching, groove wear, and fungal growth. Home-recorded cylinders, often shaved for reuse, are thin and highly breakable. Later celluloid or molded wax cylinders are more durable but still fragile.

-

-

Environmental Degradation:

-

Humidity: High humidity (>50% RH) promotes mold and fungal growth on all grooved media, especially wax cylinders and lacquer discs. Lacquer’s hygroscopic nature causes swelling and delamination in humid conditions.

-

Temperature: High temperatures (>54°F) soften vinyl, warp discs, and accelerate chemical deterioration in lacquer and shellac. Fluctuations (±2°F) stress materials, causing cracking or groove distortion.

-

Light: UV light from sunlight or fluorescent bulbs degrades vinyl and lacquer, causing embrittlement and fading of labels or sleeves.

-

Dust and Contaminants: Dirt, dust, and “paper flour” from acidic sleeves abrade grooves, causing pops, ticks, or signal loss during playback. Fingerprints introduce acids that hasten degradation, particularly in lacquer discs.

-

-

Handling and Playback Damage:

-

Mishandling, such as touching grooved surfaces or dropping discs, causes scratches, fingerprints, or breakage. Cylinders are especially vulnerable when handled by their grooved exterior.

-

Improper playback with incorrect styli (e.g., modern steel instead of fiber for aluminum discs) or heavy tracking weights gouges grooves, causing permanent damage. Dirty records exacerbate stylus wear and produce conchoidal shock-waves—mini-explosions that pit groove walls, creating audible ticks.

-

Early 78s may not play at exactly 78 rpm, and groove sizes vary, requiring specialized styli to avoid damage. Lacquer discs may play inside-out, complicating playback.

-

-

Storage and Housing Issues:

-

Acidic paper sleeves or binders degrade disc surfaces, leaving abrasive residues. Shrink-wrapped sleeves can constrict and warp discs.

-

Improper storage orientation (e.g., leaning or stacking) causes warping or groove flattening, especially in heavy shellac or lacquer discs.

-

-

Technological Obsolescence:

-

Playback equipment for wax cylinders, early 78s, or 16-inch transcription discs is scarce, and stylus availability is limited. Incorrect equipment risks damaging delicate grooves.

-

Unique recordings on lacquer or aluminum discs, often direct-cut without duplicates, face high preservation urgency due to their fragility and obsolescence.

-

Best Practices for Preserving Grooved Media

To address these challenges, individuals and institutions can adopt the following strategies for storing, handling, and archiving grooved media:

1. Optimal Storage Conditions

-

Environment: Store media at 40–54°F (4.5–12°C) and 30–50% RH, with fluctuations limited to ±2°F and ±5% RH daily. Use hygrometers and dehumidifiers to monitor and maintain conditions. Avoid basements, attics, or areas near heat sources (e.g., radiators, sunlight).

-

Light Protection: Minimize exposure to UV and fluorescent light. Store in dark, enclosed spaces or use UV-filtered lighting. Keep discs and cylinders away from windows or direct sunlight to prevent fading or material softening.

-

Shelving: Store discs vertically on enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum shelves with full-height, full-depth dividers spaced 4–6 inches apart to prevent leaning or warping. Group discs by size to distribute weight evenly. Store cylinders vertically in archival boxes with foam tubes supporting their interior to avoid groove contact.

-

Housing: Use acid-free, lignin-free enclosures passing the Photographic Activity Test (ISO 18916:2007). For discs, use high-density polyethylene, polypropylene, or polyester (Mylar D, Melinex 516) sleeves; avoid PVC or acetate. Replace acidic paper sleeves or binders, storing original artwork separately in buffered envelopes. For cylinders, use custom archival boxes with foam supports. Remove shrink wrap to prevent constriction.

2. Careful Handling

-

Handle discs by their edges at 3 and 9 o’clock positions, using clean, non-shedding archival gloves (e.g., nitrile) to avoid fingerprints or stress. Handle cylinders by their ends or interior, inserting two fingers and spreading gently to lift without touching grooves.

-

Never leave media in playback machines; return to enclosures immediately after use to prevent dust accumulation or accidental damage.

-

Inspect for signs of deterioration (e.g., palmitic acid deposits, mold, delamination) before handling. Quarantine moldy items in sealed polyethylene bags and consult professionals for cleaning, as mold is toxic and spreads easily.

3. Cleaning and Maintenance

-

Dry Cleaning: Use a carbon fiber brush (e.g., Audioquest) before and after each playback to remove surface dust. Brush gently from the center outward, avoiding groove damage. Clean the brush with its foam pad to prevent re-depositing debris.

-

Wet Cleaning: For deep cleaning, use a vacuum-based record cleaning machine (e.g., VPI 16.5) or ultrasonic cleaner (e.g., Audio Desk Systeme Vinyl Cleaner Pro) with a non-alcohol-based solution like Audio Intelligent or the Library of Congress’s Tergitol-based mix (50 parts Disc Doctor™, 50 parts distilled deionized water, 1–2 parts clear ammonia; 3–4 parts for palmitic acid). Apply the solution, work it into grooves, and vacuum thoroughly to remove all residue. For manual cleaning, follow detailed instructions to ensure complete fluid removal, as residue can redeposit debris in grooves. Avoid alcohol-based cleaners on shellac, as they dissolve the material.

-

Stylus Care: Clean the stylus before each play with a product like Lyra SPT or DS Audio ST-50 gel pad to prevent debris transfer. Avoid playing soiled records, as dust accelerates stylus wear and causes groove damage.

-

Cylinders: Clean wax cylinders with a soft, dry brush to remove dust, avoiding liquids unless advised by a professional, as wax is highly sensitive. Consult experts for mold or palmitic acid cleaning on lacquer or aluminum discs.

4. Playback and Equipment Maintenance

-

Use appropriate playback equipment with correct styli for groove type (coarse for pre-1948 discs, microgroove for vinyl) and recording speed (e.g., 78 rpm for shellac, 33⅓ or 45 rpm for vinyl, 120–160 rpm for cylinders). For aluminum discs, use lightweight fiber or wooden styli, not steel, to avoid groove damage.

-

Verify playback direction (standard or inside-out for lacquer discs) and speed, as early 78s may vary. Maintain multiple turntables or cylinder phonographs to ensure redundancy, sourcing from archival institutions or repair services.

-

Minimize playback of original or unique recordings to reduce groove wear. Use digital copies for regular access, reserving originals for creating new masters.

-

Clean playback equipment regularly, ensuring styli and mandrels are free of debris. Test equipment with non-valuable media before playing collection items to avoid damage from misaligned components.

5. Archiving and Digital Preservation

-

Digitization: Transfer audio to digital formats (e.g., WAV, FLAC) using traditional turntable playback or non-contact optical scanning like IRENE, developed by the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC). IRENE is ideal for damaged or fragile media, imaging grooves to generate digital files without stylus contact. Professional services ensure high-fidelity transfers, especially for unique lacquer or wax recordings.

-

Prioritization: Focus on lacquer discs, aluminum discs, and wax cylinders due to their fragility and uniqueness. Shellac and vinyl, often commercially replicated, may be lower priority unless rare or master copies.

-

Multiple Copies: Follow the 3-2-1 Backup Rule: maintain three digital copies, store on two different media (e.g., hard drive, cloud), and keep one off-site. Create a preservation master, duplication master, and reference copy, storing the preservation master separately.

-

Migration: Transfer digital files to newer formats every 5–10 years to avoid obsolescence. Use non-proprietary, lossless formats certified by standards groups for future compatibility.

-

Documentation: Maintain a detailed inventory using spreadsheets (e.g., Excel, Google Sheets) to track titles, formats, dates, conditions, and unique identifiers. Attach acid-free labels to enclosures, not media, and document preservation actions (e.g., cleaning, digitization) separately to avoid introducing paper debris.

6. Disaster Preparedness and Recovery

-

Prevention: Store media off the floor, away from water sources, and in secure, climate-controlled areas. Use Integrated Pest Management to deter insects attracted to wax or shellac.

-

Recovery: For water-damaged discs, air dry or pat dry with lint-free cloths, avoiding high-humidity environments. Quarantine moldy items and seek professional remediation. For delaminating lacquer discs, consult experts immediately to attempt signal recovery before further loss. Broken glass or shellac discs may be partially recoverable by professionals using optical scanning. Avoid playing damaged media on untested equipment to prevent further harm.

Tips for Long-Term Success

-

Prioritize Fragile Formats: Focus on lacquer discs (especially glass-core), aluminum discs, and brown wax cylinders, as they are most prone to sudden failure and often hold unique content.

-

Invest in Quality Supplies: Use archival sleeves and boxes from suppliers like Conservation Resources or Gaylord Brothers, ensuring they meet ISO 18916:2007 standards. Replace paper sleeves with polyethylene liners and store original artwork separately.

-

Monitor Conditions: Regularly check storage areas for humidity, temperature, mold, or pest activity. Budget for climate control equipment to maintain ideal conditions.

-

Educate Handlers: Train personnel or family in proper handling and cleaning techniques. Restrict access to originals, using digital copies for playback or sharing.

-

Plan for Digitization: Allocate resources for professional digitization, especially for high-risk formats. Non-contact methods like IRENE are ideal for preserving damaged media without further degradation.

-

Maintain Equipment: Source and maintain playback devices through archival networks or specialty repair services. Keep a variety of styli to accommodate different groove sizes and formats.

-

Protect Sleeves: Use rice paper or poly-lined inner sleeves and outer polyethylene sleeves to reduce dust and protect record jackets, as recommended by Sleeve City.

Conclusion

Preserving grooved media is an urgent task as these formats—vinyl records, shellac discs, lacquer discs, aluminum discs, and wax cylinders—face physical fragility and technological obsolescence. By implementing rigorous storage, handling, and cleaning practices, and embracing digitization, collectors, archivists, and enthusiasts can protect these sonic artifacts from deterioration and loss. Whether it’s a rare 78 rpm jazz recording, a wartime radio transcription, or a wax cylinder of a forgotten voice, preservation ensures that their sounds and stories endure. With careful stewardship, we can keep the grooves spinning, or at least digitally humming, for generations to come, preserving both the music and the tactile charm of these historical treasures.