How to Preserve Your Books and Documents

Books and documents are very difficult to move to other media, the only option is generally scanning and digitizing.

Preserving Physical Documents and Books: Safeguarding Our Written Heritage

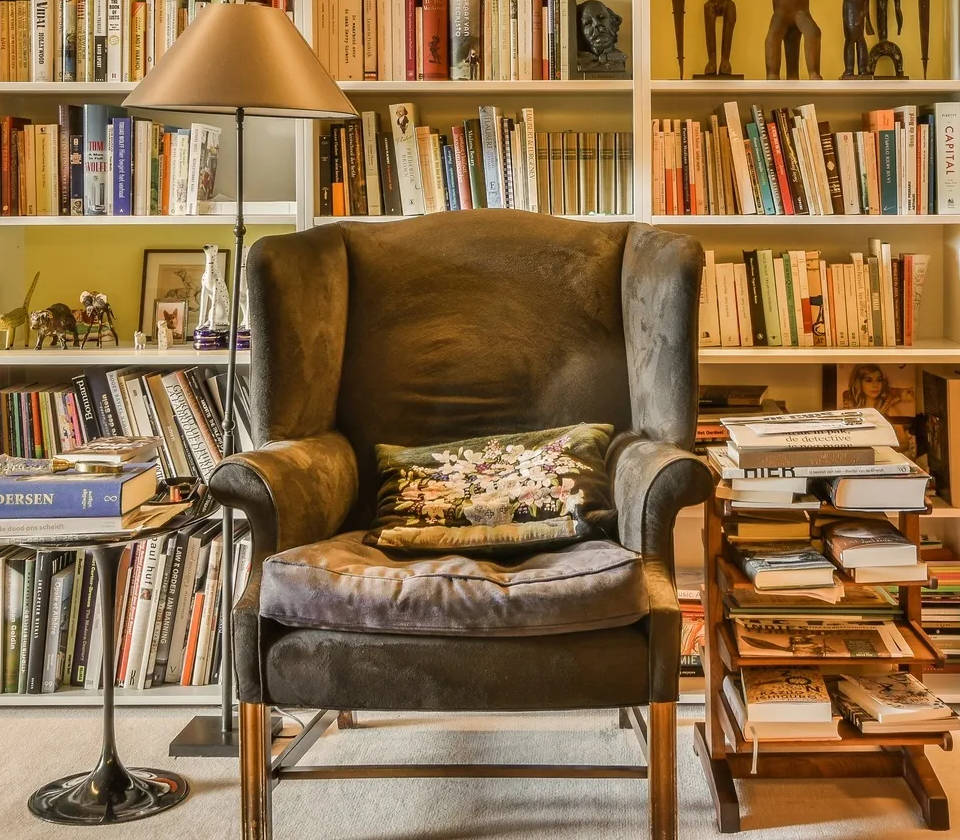

Physical documents and books—whether rare manuscripts, family letters, or cherished novels—are irreplaceable artifacts of human history, culture, and personal memory. As digital formats and e-books dominate modern consumption, the production of physical books and paper documents is declining, making their preservation more critical than ever. These materials are vulnerable to environmental damage, chemical deterioration, and improper handling, with lifespans that can range from decades to centuries depending on care. Preservation, including archiving contents onto other media, ensures their accessibility for future generations. This article explores the importance of preserving physical documents and books, details the challenges involved, and provides practical tips for extending their life and safeguarding their contents.

The Importance of Preserving Physical Documents and Books

Physical documents and books hold immense value as primary sources of knowledge, historical records, and personal narratives. Rare books, such as first editions or manuscripts with significant provenance, are prized by collectors and institutions for their historical, thematic, or authorial primacy. Everyday documents, like letters, diaries, or legal records, offer unique insights into personal and societal histories, often existing as singular copies. Even mass-produced books carry cultural weight, reflecting the aesthetics, printing techniques, and intellectual currents of their time.

Preserving these materials is essential to maintain access to information that may not be digitized or available elsewhere. For example, a 19th-century journal or a book with marginalia could provide unparalleled research value. Physical artifacts also have intrinsic worth as objects—consider the tactile experience of a leather-bound volume or the visual appeal of an illuminated manuscript. As the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Library notes, proper storage conditions can extend the life of books and papers several times longer than they would otherwise last, preserving them for future study, enjoyment, or legal purposes. Digitizing their contents further ensures accessibility, protecting against loss from physical degradation or disasters.

Challenges in Preserving Physical Documents and Books

Physical documents and books face numerous preservation risks, driven by their material composition and external factors:

-

Environmental Degradation:

-

High Humidity: Paper absorbs moisture, leading to mold growth above 65% relative humidity (RH) in warm conditions (70°F or higher). Mold can destroy paper and bindings, while humidity fluctuations cause expansion and contraction, stressing materials.

-

Heat: High temperatures accelerate chemical deterioration, doubling the rate of paper degradation for every 10°F increase. Attics or garages often reach damaging temperatures in summer.

-

Light Exposure: Ultraviolet (UV) light from sunlight or fluorescent bulbs causes fading, yellowing, or browning of paper and bindings, known as “sunning.” Even brief exposure can initiate ongoing chemical changes.

-

Dust and Pollutants: Dust accumulation fosters mold and insect infestations, while airborne pollutants (e.g., soot, chemical vapors) degrade paper and bindings over time.

-

-

Material Instability:

-

Acidic Paper: Many 19th- and 20th-century papers, especially newsprint, are acidic, leading to brittleness and discoloration. Acid migration from poor-quality paper can damage adjacent materials.

-

Adhesives and Fasteners: Rubber cement, adhesive tapes, and paper clips cause staining, tearing, or rust. Rubber bands become sticky or brittle, adhering to or denting paper.

-

Leather and Bindings: Leather bindings suffer from “red rot” (powdery deterioration), cracking, or desiccation in dry conditions. Book glue can dry out, weakening spines.

-

-

Handling Damage:

-

Improper handling, such as tugging books by their spine tops or forcing them open to 180 degrees, causes warping, tearing, or binding stress. Oils from hands, food, or drink can stain pages.

-

Overcrowded shelves or leaning books lead to permanent deformation. Using books as props (e.g., coasters, doorstops) risks structural damage.

-

-

Pests and Mold:

-

Insects and rodents are attracted to paper, especially in humid or dirty environments, causing holes, frass (insect droppings), or chewed bindings.

-

Mold thrives in high humidity, producing spores that damage paper and pose health risks.

-

-

Technological and Access Challenges:

-

While digitization preserves content, not all documents or books are digitized, and digital files face their own obsolescence risks (e.g., outdated formats, hardware failure).

-

Frequent handling of originals for research or display increases wear, necessitating protective measures or copies.

-

Best Practices for Preserving Physical Documents and Books

To mitigate these risks, individuals and institutions can adopt the following strategies for storing, handling, and archiving physical documents and books:

1. Optimal Storage Conditions

-

Environment: Store materials in a cool (65–70°F), dry (30–50% RH) environment with minimal temperature and humidity fluctuations (±2°F, ±5% RH). Use a hygrometer to monitor conditions and a dehumidifier to maintain low humidity, especially in humid climates. Avoid basements, attics, garages, or areas near water sources or outside walls.

-

Light Protection: Minimize exposure to all light, especially direct sunlight and fluorescent bulbs. Store in dimly lit rooms, use UV-filtered window coatings, or cover windows with curtains or blinds. Consider UV-protective dust jackets or archival boxes to block light.

-

Shelving: Store books upright on sturdy, sealed shelves (coated with acrylic paint or varnish to prevent acid leaching from wood). Keep books of similar size together to support covers and prevent indenting. Ensure books stand straight, not leaning, or store them flat (especially for oversized books like atlases). Leave slight gaps between books to reduce binding pressure during removal.

-

Containers: Use acid-free, lignin-free archival boxes, folders, or envelopes for documents and fragile books. Polyester (e.g., Mylar), polypropylene, or polyethylene enclosures are ideal for frequently handled items, allowing visibility without direct contact. Avoid vinyl plastics, which degrade and release harmful chemicals. For vertical document storage, use spacers or dividers in partially filled boxes to prevent sagging.

-

Isolation: Separate acidic papers (e.g., newsprint) from other materials to prevent acid migration. Insert buffered paper between documents in folders or acidic illustrations in books to neutralize acidity.

2. Careful Handling

-

Wash and dry hands before handling, avoiding lotions or creams. Nitrile gloves are recommended for extremely fragile or damaged items to prevent oil transfer, though clean hands suffice for most materials.

-

Remove books from shelves by gripping the spine’s middle, pushing in neighboring books for support, rather than tugging the spine top. Open books gently, propping covers with clean cloths or books to reduce spine stress (avoid 180-degree openings).

-

Avoid food, drink, or smoking near materials to prevent stains or contamination. Do not use books as coasters, doorstops, or presses, and avoid stacking them face-down or open for long periods.

-

Remove paper clips, staples, rubber bands, or bookmarks (e.g., pressed flowers) to prevent dents, tears, or staining. Store extraneous items in separate archival enclosures, noting their relevance to the collection.

-

Use pencils for annotations, as pens or markers can bleed or devalue items. Avoid “dog ear” folding, self-adhesive tapes, rubber cement, or leather dressings, which damage materials over time.

3. Regular Maintenance and Monitoring

-

Dusting: Dust books and shelves regularly with a soft paintbrush or lint-free cloth, brushing away from the spine and holding books tightly to prevent dust from entering pages. Clean shelves before returning books to remove dust or pest residues.

-

Pest and Mold Checks: Inspect collections periodically for signs of insects (e.g., frass, holes) or rodents (e.g., droppings, chewed bindings). Quarantine moldy items in sealed plastic bags and consult professionals for remediation, as mold is toxic and spreads easily. Maintain a clean storage area, free of food or drink, to deter pests.

-

Condition Assessments: Check for signs of deterioration, such as yellowing, brittleness, red rot, or binding cracks. Prioritize items showing early damage for protective enclosures or professional conservation.

4. Protective Enclosures and Conservation

-

Enclosures: Place fragile or valuable documents in archival polyester or paper sleeves, limiting folders to 10 sheets (fewer for high-value items) to avoid abrasion or tearing. Use L-sleeves for acidic papers instead of encapsulation, which traps acid. Store sleeved items in archival document cases or record storage cartons.

-

Boxes: Use acid-free artifact or archival boxes for rare books or documents, ensuring they block UV light and prevent leaks. Flat storage in boxes is ideal for oversized or brittle items.

-

Conservation: For damaged items, consult a professional conservator via the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) or regional services like the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center. Avoid DIY repairs with glue, tape, or lamination, which cause irreversible damage. Boxing is a cost-effective alternative to conservation for stabilizing damaged items without immediate treatment.

5. Archiving and Digital Preservation

-

Digitization: Scan or photograph valuable or frequently used documents and books to create digital copies, reducing handling of originals. Use high-resolution, uncompressed formats (e.g., TIFF, PDF/A) for archival quality. Professional digitization services can ensure accuracy for complex or fragile items.

-

Multiple Copies: Follow the 3-2-1 Backup Rule: maintain three digital copies, store them on two different media (e.g., external hard drive, cloud), and keep one copy off-site. This protects against data loss from hardware failure or disasters.

-

Migration: Periodically transfer digital files to newer formats every 5–10 years to avoid obsolescence. Use non-proprietary, standards-based formats to ensure future compatibility.

-

Inventory and Documentation: Create a detailed inventory using spreadsheets (e.g., Excel, Google Sheets) to track titles, authors, dates, conditions, and unique identifiers. Attach acid-free labels to containers, not items, to avoid damage. Document preservation actions and storage conditions separately to inform future care, avoiding paper storage with items to prevent fiber shedding.

-

Archival Repositories: For long-term preservation, consider donating originals to an archival repository with climate-controlled facilities and security protocols, ensuring professional care and public access.

6. Disaster Preparedness and Recovery

-

Prevention: Protect against fire, water, or pests by storing materials off the floor, away from pipes, and in secure, climate-controlled areas. Use the National Archives’ Integrated Pest Management guidelines to minimize pest risks.

-

Recovery: For water-damaged items, air dry or interleave with absorbent paper, avoiding high-humidity environments. Moldy items should be quarantined and treated by professionals. Consult conservators for smoke or chemical damage, avoiding irreversible treatments like lamination or freezing.

Tips for Long-Term Success

-

Prioritize Valuable Items: Focus on rare, unique, or first-edition books and documents with historical or personal significance. Items with provenance or contemporary bindings warrant extra care.

-

Invest in Quality Supplies: Purchase archival materials from reputable suppliers (e.g., Conservation Resources, Gaylord Brothers, University Products) to ensure acid-free, lignin-free enclosures. Compare prices and standards to balance cost and quality.

-

Monitor Conditions: Regularly check storage areas for environmental stability, pest activity, or material degradation. Budget for hygrometers, dehumidifiers, or UV filters to maintain ideal conditions.

-

Educate Handlers: Train family members, staff, or researchers in proper handling techniques to minimize damage. Restrict access to originals, using digital or photocopied versions for frequent use.

-

Plan for Digitization: Allocate resources for professional scanning or photography, especially for fragile or oversized items. Integrate digitization into a cyclical preservation plan, updating digital formats to counter obsolescence.

-

Seek Expertise: Build relationships with conservators, archivists, or rare book dealers (e.g., via the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America) for guidance on preservation, appraisal, or donation.

Conclusion

Preserving physical documents and books is a vital act of stewardship, protecting our written heritage from the ravages of time, environment, and neglect. By maintaining optimal storage conditions, handling materials with care, and embracing digitization, individuals and institutions can extend the life of these artifacts while ensuring their contents remain accessible. Whether safeguarding a rare manuscript, a family Bible, or a collection of letters, proactive preservation balances the tactile allure of physical objects with the practicality of digital backups. As physical books and documents become less common, their careful preservation ensures that future generations can hold, read, and learn from the tangible traces of our past.